Low levels of nitrate in drinking water can be associated with an increased risk of preterm birth and low birthweight, according to a new study.

The research published in PLOS Water by Jason Semprini, a professor at Des Moines University College of Health Sciences, Iowa, found that even a level of less than half the level considered safe by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could affect birth outcomes.

Newsweek has contacted the EPA outside of regular working hours via email for comment.

Why It Matters

The findings address growing concerns about the adequacy of U.S. drinking water safety standards, particularly for pregnant women, joining a recent study which also said that even levels of chemicals deemed safe may be harming birth outcomes.

A national study led by researchers at Columbia University found that levels of arsenic deemed safe were associated with below average birth weight and other adverse birth outcomes, and this study highlights how nitrate can have similar impacts, prompting concern that America’s drinking water standards could be harming expecting mothers, and the wider population.

Gregory Bull/AP

What To Know

Nitrate is a naturally occurring compound produced during the natural decay of plant matter in soil, and it can get washed by rain out of the soil and into lakes, rivers and streams, as well as seeping down through the soil into groundwater.

At high levels, it is recognized that nitrate causes health problems, as the compound can impact the way the body transports oxygen.

However, the new study highlights that even at low levels, below what the EPA considers safe, may still be harmful to health. Previous studies have identified risks posed to the general population, including links between drinking water nitrate and colorectal, bladder and breast cancers, and thyroid disease.

In his study, Semprini analyzed 357,741 birth records from Iowa between 1970 to 1988 and linked each birth to county-level nitrate measurements taken within 30 days of conception.

In that time frame, nitrate levels were discovered to have increased by an average of 8 percent a year, with a mean exposure of 4.2 mg/L across the births assessed.

The study found that early prenatal exposure to greater than 0.1 mg/L nitrate, which is only 1 percent of the current EPA limit of 10 mg/L, was associated with an increase in preterm birth, where a baby was born after less than 37 weeks.

Meanwhile, early prenatal exposure to greater than 5 mg/L nitrate increased risk of low birth weight babies, at less than 2,500 grams.

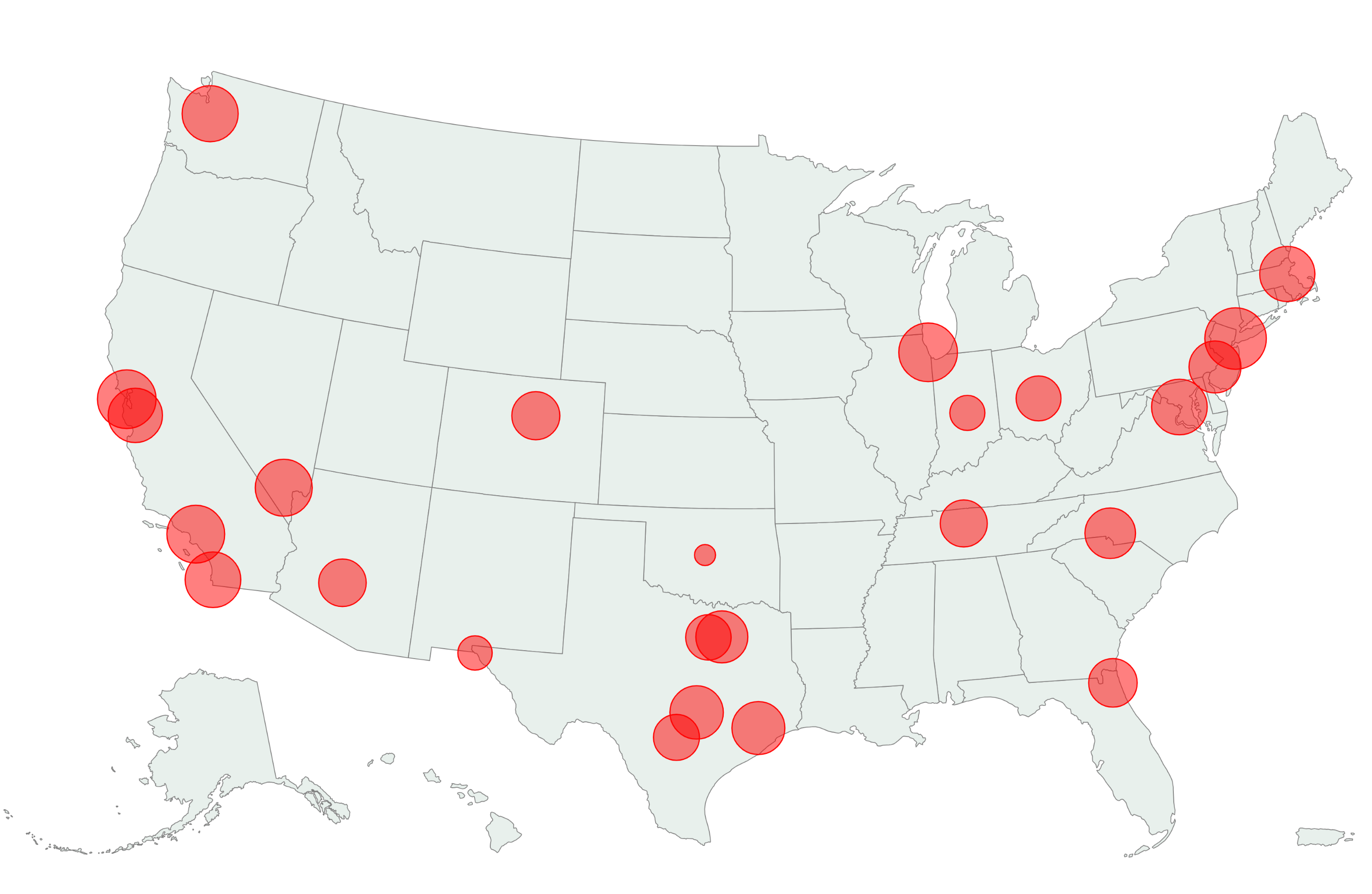

States with higher levels of nitrate in their drinking water in some areas include Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, Central California, Texas, Washington, Idaho, Delaware and Maryland, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In some parts of these states, levels of nitrate in drinking water systems were higher than the EPA’s 10 mg/L safety limit.

What People Are Saying

Jason Semprini, a professor at Des Moines University College of Health Sciences, Iowa, said, per medical news outlet medicalxpress.com: “There is no safe level of prenatal nitrate exposure. The estimated impact from prenatal exposure to nitrates reflects 15 percent of the harm from prenatal exposure to smoking cigarettes. I do not want to diminish the importance of efforts to prevent smoking during pregnancy … but, I must ask, do we give nitrates 15 percent of the attention we give to smoking?”

He added: “The regulatory threshold for nitrates in public water does not consider prenatal exposure and has not been updated since established in 1992. Ignoring the potential harm from lower levels of prenatal nitrate exposure, the current regulatory standards are not adequately protecting America’s mothers or children.”

What Happens Next

As the study was limited to one state, making it limited in scope, national and further research is needed to determine the full impact of low-level exposure to nitrate in drinking water systems on public health.

Reference

Early prenatal nitrate exposure and birth outcomes: A study of Iowa’s public drinking water (1970–1988): Semprini J (2025). PLOS Water 4(6): e0000329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pwat.0000329